Intergenerational Trauma: Q&A with Sherese Ezelle, LMHC

Throughout history, minority groups have endured a multitude of severe traumas and discrimination. From colonization and mass genocide to land displacement and slavery, the list goes on and on. And while legislation has since been created to protect the rights and freedom of these populations, the impact of these traumas continues to be felt to this day. One study, for instance, found that the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors were overrepresented by about 300% in referrals to psychiatric care. Likewise, several studies of Native American populations have found that decades of assimilation, violence, and loss have been associated with behavioral health challenges in later generations including increased risk of substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

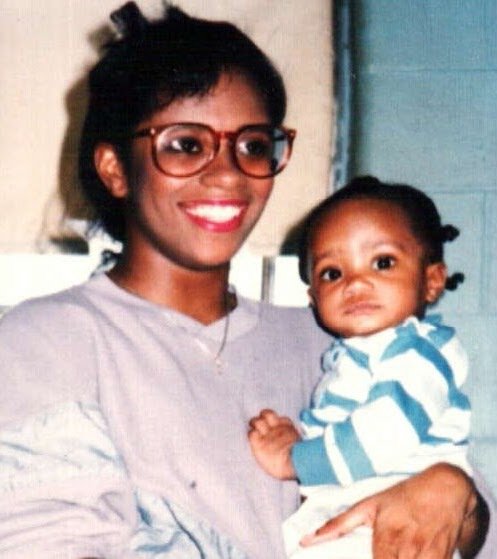

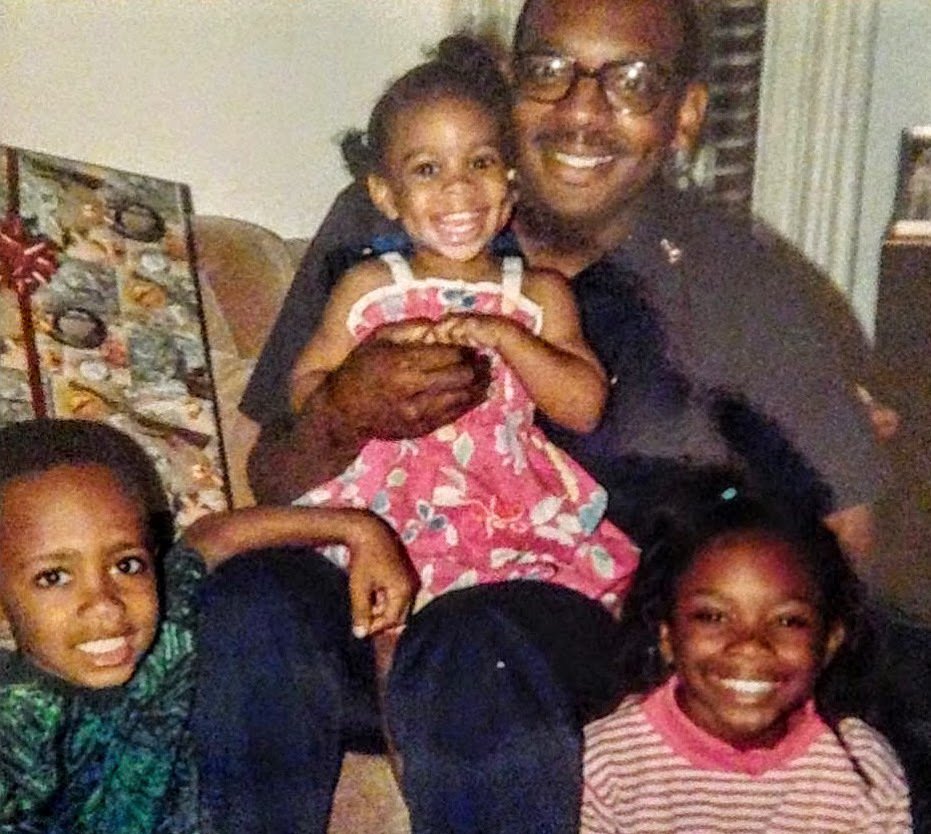

This theory that trauma can pass down from one generation to the next is known as intergenerational trauma. With July being Minority Mental Health Awareness Month, we sat down with Mental Health Specialist Sherese Ezelle, LMHC to discuss the impact of intergenerational trauma on people of color and their health. Ezelle, who is African American herself, works with members at our Google site in Seattle.

Q: What is intergenerational trauma?

A: Intergenerational trauma refers to the ways in which trauma experienced in the past can impact the health and well-being of future generations, trickling down to family members. For indigenous people, for instance, the trauma of being enslaved and losing property and freedom and various other experiences has created a typical type of conscience for members of that population living today. These traumatic experiences continue to have a direct correlation to the mental health and well-being of their children. Some of these constructs have led to symptoms such as denial, agitation, anxiety, depression, mistrust, and guilt. The behaviors of children of those that have experienced trauma are based on the parenting and attachment styles that were experienced many, many generations before. In Black culture, there are a multitude of traumas that would lead to intergenerational trauma. I can use myself as an example. My family, historically, was enslaved. My great grandparents were sharecroppers. Lacking capital and land of their own, former slaves were forced to work for large landowners. So they lived on property owned by someone else and tended the fields, raised animals for food, and picked cotton and peanuts. Once my great grandfather died they were asked to leave. So the trauma my grandmother experienced and the behaviors and attitudes she learned to cope with that trauma have trickled down to my mom and down to my siblings and I.

Q: Your personal experience is unique even to many people of color. How do you feel that your grandmother’s experience impacted your mom and then impacted you and your siblings?

A: As a family we talk about this kind of stuff all the time. My grandma has passed, but we often think about how my grandma’s experience impacted us growing up. Things she’s taught us and my mother, affected how my mom raised me, and how my siblings and I interact. My great grandparents made very little and raised what they ate so they did not have much. That history definitely impacted how my mom managed our finances and resources. We were really mindful of what we had because my grandma and my great grandparents didn’t have a lot. We grew up hearing about how my grandma didn’t have shoes for school because her parents had limited income and had 13 children to take care of. My grandma had roughly a third grade education because her family could not afford to send her to school for long. Eventually, she was able to obtain some education later in life and was a nursing assistant when she passed. So the importance and value of education was really reinforced with my mom and then onto my siblings and I and so on. My mom was hyper focused on us going to school because there were barriers back when my grandma was able to. She wanted us to be successful and be able to set ourselves apart. That’s something I still attribute to who I am. Being educated and being able to overcome those barriers is a big part of my identity and it stems pretty deeply. This is just one example of how trauma shapes out in a family and affects their behaviors, but everyone has their own experience and stories.

My mom recently shared her own experience with intergenerational trauma living in the “projects” in Chicago with my grandma. She said, “I didn’t realize how traumatized I was from all the things that happened to us in the projects. It was just the way it was.” My grandma worked at nursing homes on the night shift and would tell my mom that once she closed the door at night, not to open it. My mom said, “And that’s what we did, we stayed inside. She did that to keep us safe even though walking to the rail station at night to get to work was dangerous for her. She did that for us.”

Q: Do you feel like that trauma has impacted your own mental health?

A: Yes, definitely. Throughout my life, I have always felt this pressure to overachieve. I am a perfectionist because of that and it does hinder me in a lot of different ways. Throughout my schooling, I felt there was some sort of trauma if I got a B or C and that I was letting my family down if I got anything other than an A. I remember when I got my first A minus, I literally created a whole list of reasons as to why I should have gotten an A. To me, getting an A minus was like getting a B plus, and a B plus was a B and so forth. Because that importance of education was instilled into me, I felt like I had to be the best for my family. I have to make sure that they see that everything they went through was for a purpose. That’s a constant thought that runs through my mind — this feeling that all the struggle and fight they went through has to all make sense. What I’ve done, what they’ve done for me, it has to have been for something.

Q: How do you think that experience has impacted your philosophy of care?

A: I think it’s really made me focus on the individual person and the importance of their unique experiences. Because I’ve faced my own intergenerational trauma, I can recognize our shared experience, but also appreciate their personal experiences. I remove myself and really look at them as a person with unique experiences that make them who they are. Meeting them where they are is the most important part of my patient-centered work. I think my experience has also informed the way that I think as far as therapy being a partnership. It’s so important for each part of that partnership to be willing to give and take. I can help a patient understand their behavioral health condition and let them ask me their own questions. I can support them by saying, “Here are some things that have worked for other patients, and here are some that may work for you.” I believe my understanding of this partnership stems from the fact that my family is so linked and in true familial partnership with one another. I can see the benefit and richness of this type of collaborative care.

Q: Why do you think it’s important to consider intergenerational trauma when caring for people of color?

A: It’s important because it allows us to see the whole person. If we don’t acknowledge what they’ve been through generationally, then we’re missing a huge part of who they are. We have to treat the whole person. I think one of the reasons I enjoy therapy is because I’m able to partner with physicians like the ones at One Medical who are looking at every part of the person. A primary care provider at One Medical will see a broken bone and question the root cause of the problem. Was it from some form of trauma, abuse, or neglect? If so, I can step in and look to support them and help the patient get to a safer environment and address the associated behavioral response to that trauma. We work together. The provider can treat the physical side, while I can treat the behavioral health side. I think it’s important to look at every piece of the human being in order to treat them as such. If you leave those pieces out, are you treating the human? Or are you treating that specific condition?

Q: How can intergenerational trauma impact the mental health of people of color?

A: I think it separates us from really being our true selves. This history and trauma is a big part of us so when it’s not addressed or not looked at, it can be very isolating. Just being asked these interview questions, for instance, helps me feel better and more connected to who I am. It feels good to be able to share such a big part of me with others and have the chance to discuss it. But how many people of color get this experience? How many are stopped and asked about their family history and trauma? I think it creates a sense of isolation and that can be damaging to your mental health because again, your sense of self is so important to your well-being.

Q: How do you think this intergenerational trauma has affected people of color’s approach to healthcare?

A: Well in the past people of color couldn’t find providers that looked like them or understood their struggle. That was a huge barrier — feeling like they didn’t have anyone that looked like them that they could relate to. Many people of color think, “Well if you weren’t able to help my grandmother or my great grandmother, how are you going to be able to help me?” Also financial barriers. Healthcare and behavioral healthcare, in particular, were not things many people of color had the luxury of affording. They were not going to stop going to work, where they only earned enough as is to maintain, to get behavioral health care. In addition to that, there is the stigma. Most of my extended family and members of my community would say things about therapy and behavioral health care like, “I’m not crazy, why do I need to go there?” Historically, there has been this thought in the Black community that if you get behavioral healthcare, you are immediately crazy. That’s something that’s been passed on from their parents, and their grandparents and so forth. If you go to a behavioral health provider, you are instantly crazy and therefore many people of color can’t see the value. Why would I take time off of work to see someone that’s going to deem me crazy? How is that going to help me feel better? I think there is also a sense of guilt. There is this thought among people of color that it’s not fair to have these opportunities and care at their disposal when their grandmother and great grandmother didn’t. How is it okay for me to receive this type of care when they didn’t? As a therapist, it’s important for me to break that cycle of thought that you should not obtain services or care just because your family didn’t or wasn’t able to. I want to empower BIPOC to bring what they’ve learned in therapy and behavioral health care back to their family. While it’s important to learn from your family’s history and backstory, it’s equally important to pull from the present to heal.

I also think people of color have a hard time trusting systems. Let’s be honest, in our current culture of violence and mistrust, systems have failed us. As a person of color, there is this implicit, internal dialogue with each medical concern, including behavioral health services. The internal dialogue typically sounds like, “How many hoops am I going to have to get through? And once I get there, what is that person going to tell me? Are they going to tell me that I have to have this surgery? Or am I going to have a choice in my healthcare? Can I trust that this system is going to support me?” Right now, many people of color look at healthcare as another system that will fail them. However, at One Medical, we are separating ourselves from typical systems. We wear casual clothes, we introduce ourselves by our first names, and allow individuals to really ask questions without feeling as though they’re inferior. We’re equal and meet them where they are. That’s what separates us from a typical system and getting that message out there is really important.

Q: Is this something you’ve experienced with your patients? Do you feel like your patients are feeling the impact of intergenerational trauma?

A: I’ve had patients sit with me and tell me that I’m the first Black provider they could find and that’s what they’ve needed — someone that looks like them and can connect with them and their story. As a provider of color, I have that experience often. Especially being a female provider who is Black. More women that have experienced severe trauma are willing to meet with me because of my race and gender. In my career this is my most typical clientele — women of color who have experienced severe trauma that feel like they can confide in me and that I can relate. That ties back to what their providers have looked like in the past and the systemic discrepancies they’ve experienced. Historically, providers didn’t look like them. And that’s what people of color today are expecting. They are expecting to sit in front of another white provider who is going to tell them what to do and what medications to take, without the ability to ask questions and be an active part in their healthcare. We’re really in a day and age where we can take control of our healthcare and this has not been the average experience for a person of color. If a person of color is reaching out for help, it can be traumatic to not be able to find anyone that looks like them, especially if everyone in their immediate support system and community does. Especially right now with current events. We expect the police and people of authority to protect us. And when we see that there are white police officers who are not protecting us, we lose trust in that system and those associated systems. Being put in front of a white provider is similar. Are we going to be heard? Are we going to be listened to? Are we going to be marginalized and put down because we don’t know something? Do you really want to talk about how you’re eating habits with someone who doesn’t doesn’t understand that soul food is a large part of our connection to each other and community? They’re going to tell you not to eat soul food staples and meals we’ve grown up with that bring us a sense of comfort. Then we are faced with the task of wanting to follow the advice of the provider while keeping true to our traditions. So the question then becomes, “What I can substitute that’s going to make me feel like I’m at home? Have my lovingly prepared food choices been incorrect this entire time?” It’s that representation. Even hearing that I’m the first provider of color they could find puts a lot of weight and pressure on me. With my own intergenerational trauma, I feel this immense sense of obligation to my people and my family to be this awesome Black provider.

Q: Have these patients shared what their experiences with other white providers have been like? Why did they want to connect with you over somebody else?

A: There are two sides to it.There is the one side where certain people of color don’t want to even see a provider of color. And that has to do with the inclusionary thought process that they received before, in which a provider of color has tried to interject their own experience onto that patient. So sometimes they’ll come to me and defensively start the session by saying, “You’re not going to tell me what to do, are you?” or “Don’t tell me about your experience” because of that specific experience. On the other side though, many patients of color have told me they’ve experienced providers — typically white providers —that have belittled them or have tried to tell them what they are feeling, without really giving them the chance to speak for themselves. People of color historically have felt as though their choices have not been their own. So when they see me they may feel like it’s a breath of fresh air. They want to have a choice in their healthcare and be explained the reasoning behind things. Many people of color feel like they’re being assessed and treated as soon as they enter the room. Many white providers will immediately diagnose them with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder because of traumas they may have experienced that have nothing to do with their current symptoms or concerns. That’s something expressed to me regularly.

Q: What can white providers do to help the patients of color feel more comfortable?

A: Providers can really just listen and take the time to explain what they are doing and the reasons behind doing so. Just explain every step. There seems to be a fear among many patients of color of appearing uneducated. We don’t want to seem inferior in any way, given that we have often been treated as such in the past. So even if we don’t ask the questions, explain anyway. Talk to us and just be clear about the fact that this is our healthcare. Empowerment is huge. As a provider of color, I think about how I can empower my patients to take control of their own healthcare daily. I continually remind my patients every session of the progress they’ve made, what they’ve done well, and how important it is that they’ve opened up to me. It’s important to be an empathetic listener and validate their concerns. Answer questions even if they’re not asked and be fully transparent with everything you are doing. Even if it’s something that seems minimal to you as a provider, your patients may not know. And if they don’t know, historically, they’re not going to ask.

Q: What steps can patients take to protect their health in the face of intergenerational trauma?

A: Since July is Minority Mental Health Awareness Month, I think this question is of particular importance. First, recognize that this is a part of you and it’s okay. Also, feel empowered. Let people know that this is your healthcare and you want to be part of it. If you don’t feel empowered, look for people you can reach out to for inspiration. Identify people who are supportive and might be able to go on this medical journey with you. And educate yourself as much as you can. Know that if you don’t know something or are unclear, it’s okay to ask questions. We’re in a different space than our ancestors where it’s okay to ask questions. Find your voice, look for help from those around you, and be confident that there are people here to support you. Minority Mental Health is important. It is important to begin to normalize the experience of BIPOC as active participants in maintaining mental wellness. The need for behavioral health support is not a character flaw. To seek such help shows great strength and resilience and can bring us to a place of holistic healing.

The One Medical blog is published by One Medical, a national, modern primary care practice pairing 24/7 virtual care services with inviting and convenient in-person care at over 100 locations across the U.S. One Medical is on a mission to transform health care for all through a human-centered, technology-powered approach to caring for people at every stage of life.

Any general advice posted on our blog, website, or app is for informational purposes only and is not intended to replace or substitute for any medical or other advice. 1Life Healthcare, Inc. and the One Medical entities make no representations or warranties and expressly disclaim any and all liability concerning any treatment, action by, or effect on any person following the general information offered or provided within or through the blog, website, or app. If you have specific concerns or a situation arises in which you require medical advice, you should consult with an appropriately trained and qualified medical services provider.