Racism & Asian American Mental Health: Q&A with Annie Chan, FNP

Over the last year, the U.S. has seen a dramatic surge in violence, harassment, and hate crimes against Asian Americans amid the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between March 2020 and February 2021, nearly 3,800 hate incidents — ranging from racial slurs and verbal harassment to shunning and physical assaults — were reported against Asian Americans, according to the advocacy group, Stop AAPI Hate. The New York City Police Department also reported a 1900% increase in ant-Asian hate crimes in the last year alone.

Now, public health experts worry the surge could have long-lasting health ramifications. One study, for instance, found that Asian Americans who experienced COVID-19 related discrimination also experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression. Likewise, a growing body of research suggests that chronic stress induced by frequent racist encounters, can increase risk of depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, inflammation and other illnesses. With this in mind, we sat down with One Medical provider, Annie Chan, FNP-C to discuss her personal experience as a Chinese American woman, as well as the potential health impacts of such discrimination. Chan serves as the chair of One Medical’s Employee Resource Group for Asian, Pacific Islander, and Desi Americans and provides virtual health care to patients in the Chicago, Boston and New York districts.

Q: What is your experience being Asian American? And how has the recent surge in anti-Asian hate impacted you?

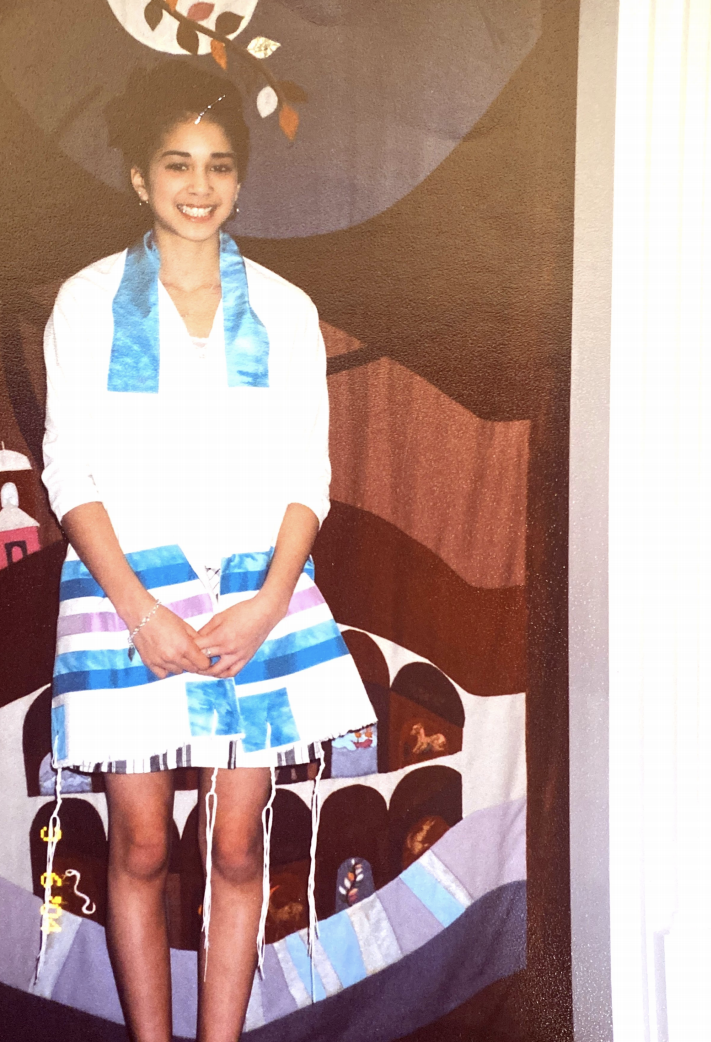

A: My father is from Hong Kong, I'm first-generation on his side, and my mother is Jewish. I’m the third of four kids and by the time I came along, managing multiple activities like martial arts, Hebrew school, Chinese school, and Sunday school was just not feasible. Our exposure to “being Chinese” was different from that of our Jewish, white counterparts. We would go to Hong Kong and we would see my grandparents, Amah (grandmother) and Agong (grandfather). Food was and is a big part of my Chinese identity as it is for a lot of assimilated kids. I don’t speak Mandarin or Cantonese, but that does not affect the extent to which I identify as Chinese or am perceived as “other”.

For a long time I grappled with that double tension: Jewish and Chinese. I struggled with having the last name, Chan. Kids and adults would give me a hard time about it. I remember being told how lucky I was to not look really Chinese or that I was “pretty for a Chinese girl”. I really internalized that until I began to examine my identity as an Asian American woman later into adulthood. Now I think about how proud I am to be a Chan.

We can be these complex creatures. We can be both. But despite knowing this, limiting thoughts have emerged a lot for me recently. Thoughts like, "I'm not Chinese enough" or "This pain can’t be mine, I’m not allowed.” To come back to your initial question, the surge in anti-Asian hate has caused me a tremendous amount of pain and insecurity. I find myself having to justify this grief because of the different worlds I occupy as being both Asian and American. This swell of discrimination has really reinforced that split. I feel so caught up in that double tension, pulled one way and then another. It opens old wounds and scratches new ones. But it’s also set me on a path toward healing.

Q: Discrimination against Asian Americans has existed long before the coronavirus pandemic. What changes have you noticed over the last year with the pandemic and how has this compared to your experience in the past?

A: I think there exists this somewhat dangerous thought that healing is linear, including healing from our global unspeakable past. It is easy to believe that the “further” in time we get, the further we are from slavery, genocide and deeply discriminatory immigration policy. But this is not the case. The political climate that allowed for phrases like “China flu” and “kung fu flu” to be part of our normal vernacular permitted violence against a minority group in a really explicit way. The WHO states that disease names can't include geographic locations. They can't include people's names, a species or a class of an animal or food, a cultural population and industry, or any kind of reference to something personal. Yet here in the States, that is exactly what happened. That really opened the door here. Anti-Asian sentiment might not necessarily be so new, but the door was flung open on it with the pandemic. The same amount of learning, growth and work needs to be done that's always needed to be done. But I think in this last year, permission has been granted to put a target on this community's back. So the urgency for that same work has been escalated.

With regard to my past experiences and how that compares to now, I feel more unsafe, more on edge. There is fear for my safety, for that of my father’s and my siblings in a way that feels bigger than just the c-h-i-n-k word (which is pretty big having felt its impact myself). When I was a kid being made fun of, the instigators were not motivated by fear in the way they are now. So their ammunition was slightly less dangerous: insults and snide remarks. Now, the motivation of the attacker is to punish the community perceived as being responsible for a global crisis. And so the manifestation of that motivation is so tremendous. It’s violence. The fear of physical harm is novel to my experience compared to the past.

Q: You mentioned some of the microaggressions like patients referencing fear of certain neighborhoods during COVID. How did you handle those types of comments when managing patients?

A: I didn’t really handle these comments with patients. I didn’t know how. I was shocked. I live in Tennessee now, but I lived in New York for seven years, and am proud to be a New Yorker because of the diversity that comes with living there. But at the beginning of the pandemic, I was floored hearing a lot of patients saying things like, "My subway commute passes Canal Street. I'm scared of seeing all those Chinese people," or "I went to China town the other day, am I sick now?” At that time I was on our virtual team. We were being inundated with video chats, and it was so busy. We tried to all take time for ourselves, but we were just so overwhelmed. I felt like I was just keeping my head above water. I didn’t know how to respond or what to do with the sadness comments like those evoked. So I just kept working.

Now I look back and wish I had been able to facilitate a conversation with those patients and say, "Hold on. Can you understand why referencing Chinatown in Manhattan is offensive to a particular community of people that are New Yorkers, just like you?" I feel sadness, regret, and hurt around that. I also feel motivated now to help my colleagues identify and sort of interrupt those conversations. That's a really hard thing to do, because the emotional response is so overwhelming.

Q: How is this racism, discrimination, and violence a public health issue? How can this impact one’s mental and physical health?

A: The CDC defines public health as “the science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities. This work is achieved by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing, and responding to infectious disease.” The Stop AAPI Hate National Report documented 3,795 hate incidents only between March 19th, 2020 and Feb 28, 2021. These anecdotes range from New York and San Francisco to Virginia and Texas, and they are pervasive. It's in the workplace. It's in a gymnastics gym, where the owner wouldn't accept a woman’s child based on the mom's last name. It’s in restaurants and small businesses. Racism is an issue of public health because inciting fear in a particular identity group threatens and diminishes the wellbeing of a community.

The takeaway from an assault like those described in the Stop AAPI hate national report is fear and stress. As clinicians, we know what chronic stress does to the body. It makes us more prone to cancer and degenerative diseases and can lead to weight gain, decreased immune function, increased blood glucose levels, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression. I think the impact is tremendous.

Q: How do you think discrimination and hate against Asian Americans, and the recent news coverage of that racism and violence, has impacted your mental health?

A: My anxiety is up. I think about my dad who is a podiatrist. He owns a small practice just outside of Boston, and he does a lot of pro bono work in Chinatown. I am gutted when my imagination infers that my father and his practice may be targeted based on his race. I feel frozen with fear and an overwhelming desire to hide and at the same time protect my father. A person who for so long served as my protector. I’m sure I am not alone in this frozen state of anxiety. Which is what drives me to speak these words anyway, despite my fear. To make these overwhelming emotions a little bit less lonely.

With regard to the media coverage and its effect on my mental health; I think it’s more about the lack of news that’s affected me. I wish we were talking about this more.

Q: What advice would you give to Asian American patients who may be experiencing feelings of anxiety, stress, or depression related to the recent news coverage and surge in anti-Asian hate? Or who have experienced discrimination themselves?

A: I recommend self-compassion first and foremost. I think there's this negative connotation around self-pity. It's very un-American. But I would encourage more people to demonstrate self-compassion. Say to yourself, "I'm so sorry this is happening. You're not deserving of this pain." We have to honor this fear and despair before we can heal from it. There is no joy without pain. So I think the first step is going inward and recognizing that. Then to begin healing, identify the counter emotions to fear and stress, which, to me, are peace and joy. So then I would ask you: "What brings you joy? What brings you peace? What brings you security?" Honor that pain while moving through it to find peace and joy.

I recognize too that this is not a modality for everyone. Demonstrating self-love and subsequently seeking peace and joy is easier said than done. Sometimes the solution is pharmacotherapy and a licensed therapist. Anxiety and depression not only could be exacerbated through acts of micro/ macro aggression toward our community, but stress can also trigger a mental health crisis. Trauma can provoke a hypo or hypermanic episode in a patient with known or unknown mental health history. My advice would be to bring this to your primary care provider regardless. We can help you find the right treatment or guide you with the appropriate next steps. Stress wreaks such incredible havoc on our physical bodies. I hope you can trust me and your primary care provider to hold this pain for you temporarily and help tailor a plan to begin healing.

If you or someone you loved is struggling with their mental health, Mental Health America has compiled a list of mental health resources specifically for the Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

If you ever have thoughts of harming yourself or that life is too hard to keep living, or you’re in crisis and need to speak with someone immediately, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1(800) 273-8255, or the National Crisis Text Line (text START to 741-741). These services provide free, confidential crisis counseling 24/7.

Most importantly, schedule a remote or in office visit with your primary care provider. For more information on One Medical can help with your mental health concerns, read here.

The One Medical blog is published by One Medical, a national, modern primary care practice pairing 24/7 virtual care services with inviting and convenient in-person care at over 100 locations across the U.S. One Medical is on a mission to transform health care for all through a human-centered, technology-powered approach to caring for people at every stage of life.

Any general advice posted on our blog, website, or app is for informational purposes only and is not intended to replace or substitute for any medical or other advice. 1Life Healthcare, Inc. and the One Medical entities make no representations or warranties and expressly disclaim any and all liability concerning any treatment, action by, or effect on any person following the general information offered or provided within or through the blog, website, or app. If you have specific concerns or a situation arises in which you require medical advice, you should consult with an appropriately trained and qualified medical services provider.